When I’m in the car, I almost always have a wine podcast playing. This drive was no exception. With the seatbelt fastened and the road unwinding ahead, I listened as James McNay, my friend and fellow Italian Wine Ambassador, guided the conversation on Ambassador’s Corner for the Italian Wine Podcast.

His guest was Attilio Pecchenino.

The exchange was pleasantly familiar. Terroir, tradition, Nebbiolo, Barolo as it is supposed to be discussed. I was listening closely, almost on autopilot, until James asked a question that shifted the entire frame of the conversation.

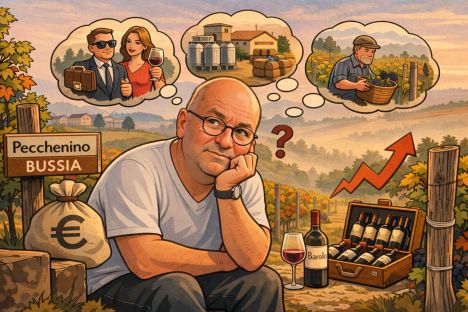

“Attilio, what is a hectare of Barolo vineyard worth today?”

Attilio said that in 2009 he had bought a parcel in the Bussia cru for around €300,000 per hectare.

Today, he replied without a pause, it is closer to €3,000,000 per hectare.

Three million euros.

For a single hectare.

In that moment, it became unmistakably clear that this story is not only about wine. It is no longer confined to grapes, vinification, or vintages. It is about capital, structural scarcity, and the defining question of the next era in the Langhe. Who will still be able to make Barolo, and on what terms?

📈 Why Barolo Vineyard Land Has Become a Luxury Asset

That Barolo vineyard land now costs a fortune is no coincidence, and certainly not a passing phase. It is the result of three forces that have been moving together for years: structural scarcity, tight regulation, and a level of demand that simply holds.

To begin with, Barolo is geographically small. The appellation covers only a limited run of hills across eleven communes, and there is very little room to expand. On top of that, new plantings are tightly controlled at European level. Through the planting authorisation system, annual vineyard growth is effectively capped at around one percent. In a zone where almost every suitable slope was planted decades ago, that means something very practical. Almost no new land is added to the Barolo equation.

And yet the world’s appetite for Barolo has not eased. Year after year, production remains broadly in the same range, often estimated at around thirteen million bottles, while Barolo has only strengthened its place on international wine lists and in collectors’ cellars. It has long since broken free of the “classic Italian red” category. Today it is treated as a global reference, spoken of in the same context as great Burgundy or top Napa.

What is striking is that this prestige has not translated into an equivalent surge in the wine’s underlying producer-side value. The price per hectolitre of Barolo, a useful proxy for the wine’s value at origin, has remained remarkably steady in recent years, hovering around €900 to €1,000. For investors, that matters. It suggests a market that is not only prestigious, but also predictable.

Then there is Barolo’s own brand power. When someone buys a Barolo parcel today, they are still investing in a product, wine made from grapes grown on a specific slope. At the same time, they are buying into an international reputation built on origin, prestige, and historical depth. In that context, each hectare works like a lever. Limited supply, structural scarcity, and global reputation keep reinforcing one another. The outcome is hard to avoid. Land prices are not rising because farming suddenly became more expensive. They are rising because Barolo itself has become an exceptional and highly coveted possession.

🔎 What Does It Cost Today?

Translate that dynamic into real numbers and you quickly arrive at the different crus. Not every hectare of Barolo is priced the same. Location, reputation, and scarcity are decisive. Conversations with producers and recent market analysis suggest the gaps are now substantial.

Indicative market values for Barolo vineyard land (2024):

- Bussia (Monforte d’Alba): €2.5–3.0 million per hectare

A blue-chip site with iconic producers; the reference point for Monforte. - Cannubi (Barolo commune): €2.0–2.5 million per hectare

Historic cru, referenced as early as 1752; a powerful name with slightly broader availability. - Ravera (Novello): €1.2–1.8 million per hectare

Rapidly rising in esteem; attractive to newer investors. - Vigna Rionda (Serralunga d’Alba): €2.0–3.0 million per hectare

Extremely limited supply; discreet transactions can exceed these levels.

Sources: CREA, Gambero Rosso (2024), interviews with producers.

💼 Case Study: Vietti

“A brand can survive, but a wine style is alive.”

I still remember clearly how I used to drink Vietti. Their Rocche di Castiglione was, for me, the textbook example of what Barolo can be. Complex, refined, and at the same time unmistakably rooted in its place. These were wines with tension and personality, wines that seemed to hold a line between polish and stubbornness.

So when it became public in 2016 that Vietti had been sold to the Krause Group from Iowa, it landed like a shockwave in Barolo. It was one of the first times a historic Barolo estate, built and financed over generations within a family, passed entirely into foreign hands. On paper, everything looked reassuring. The winemaking team stayed. Mario Cordero, who had long been responsible for vinification, remained in place.

And yet wine is rarely only the sum of technique.

In the years after the takeover, I began to notice a shift in the glass. The wines were still undeniably good. Technically precise, clean, consistent. But for my taste, they felt different. Less inner tension, less personality. More polished, smoother, more obviously “correct”. As if some of the wine’s friction had been traded for international readability. It was still Barolo, but it felt less insistently Barolo.

That impression took on a human face at Vinitaly 2025. There I met Caterina Cordero, the family’s daughter, who now runs Cordero San Giorgio in Oltrepò Pavese with her brothers. She spoke openly about the changes at Vietti, about how much she missed Barolo, and about her hope of one day being active in the Langhe again. Not with bitterness, but with a visible sense of longing.

She did not come across as someone who had “lost a project”. She came across as someone who missed a place. And that is precisely why this case matters. Behind an acquisition there is never only brand strategy or investment logic. There is also a sense of style, a family history, and a way of working that does not always travel cleanly from one context to another. Even when the winemaker remains the same, the wine can change when the world around it changes.

🍇 Consequences in the Vineyard

The list of buyers in Barolo has become surprisingly diverse. Alongside the familiar family names, rooted in these hills for generations, new players are showing up more and more often. Luxury groups, private equity, even international hospitality companies are looking at Barolo as a safe and prestigious place to put their money. That flow of capital is not automatically a bad thing, but it does change the region’s rhythm.

You see it most clearly in ownership. For families who have worked the same steep slopes for decades, today’s land prices are becoming harder and harder to square with succession. When a hectare is worth millions, the estate does not only gain status. The financial pressure around handover rises as well. Inheritance tax is calculated on market value, while the cash in a wine business is often limited. The wealth sits in the vineyard, not in the bank. Add the reality of having to buy out brothers or sisters who are not active in the domaine, and the sums quickly become too heavy, even for healthy estates. Banks look at cash flow, not at heritage.

In that context, selling becomes less of a choice and more of a necessity. Not because families want to stop, but because the numbers start pushing them there. For young winemakers, the same prices create a near-impossible barrier. Barolo becomes less a place you can grow into step by step, and more a place you can only enter if serious capital is already behind you.

With new ownership also comes a shift in how winemaking is approached. In family estates, the vineyard is usually the starting point, with decisions shaped by experience, intuition, and pride in the land. In larger structures, the focus more often moves toward efficiency and control. Money goes into modern cellars, precision tools, hospitality, and international marketing. That can raise standards and professionalise the region, but it also changes what gets valued most. Winemaking becomes part of a broader business model, where consistency and scale can matter more than a personal touch.

And that has consequences for how Barolo is made today. Terroir does not disappear, but it starts playing a different role inside a tighter economic frame. The question hanging over these vineyards is not whether Barolo will lose quality. The real question is how much room will remain for identity, for interpretation, and for the kind of individual voice that made so many of us fall in love with Barolo in the first place.

👃 What Does This Mean for What’s in the Glass?

For the drinker, these changes show up first on the label. In Barolo, origin is carrying more and more weight, and you see that in the rise of the Menzioni Geografiche Aggiuntive, the MGAs. Producers increasingly choose to state exactly which cru, or even which parcel, their grapes come from. Not only out of pride or conviction, but because that kind of precision now has real value. A name like Bussia, Cannubi, or Vigna Rionda is no longer just a place on a map. It has become a clear signal in the market.

That evolution mirrors the jump in vineyard prices almost directly. As hectares become rarer and more expensive, the urge to show that value openly grows stronger. MGAs are more and more used as price anchors. They help justify higher bottle prices and they create a hierarchy inside an appellation that many people used to think of as one whole. Barolo becomes less of a single category and more of a layered landscape, where origin, reputation, and scarcity keep feeding each other.

But it does not stop at the label or the price list. It reaches into how terroir is talked about, and sometimes into how it is handled. Terroir once meant accepting the limits and the character of a specific slope. Today there is a risk that it turns into a story that needs to be easy to sell. Origin still matters, but more and more for what it adds commercially. Variation, risk, and vintage moodiness, things that used to be part of proud winemaking, can give way to consistency, predictability, and a style that reads well internationally. Anything that falls outside that frame gets smoothed out.

In the end, you can taste that shift. Many wines become more correct, cleaner, technically spotless. Yet some lose a bit of their tension and their edge. Not because they are made with less skill, but because the focus changes. The wine no longer has to speak first and foremost about where it comes from, as long as it remains recognisable and sellable within an international fine-wine language.

That is why Barolo now finds itself in a delicate place between return and identity. The challenge is not quality, that part is not in doubt. The challenge is meaning. Because when origin becomes only a marketing tool, rather than a guide for decisions in the vineyard and cellar, the soul of winemaking can slowly start to fade into the background.

🔮 Where Barolo Goes Next

The question of where Barolo is heading is not theoretical. You can feel it today in the vineyards, in the cellar, and in the market. One possible future is already easy to imagine, and it is the one many people quietly fear. Barolo becomes even more exclusive. In that scenario, it follows the road Burgundy has been on for years. The best crus become rarer and more expensive, prices keep climbing, and the bottles slowly drift out of the everyday reach of the lover of Barolo. Real growers will still be there, but their wines increasingly become things to collect and invest in. Barolo remains great, but it becomes harder to live with.

Another direction is scale and sameness. Larger groups take a stronger and stronger position, professionalise the region even further, and lift everything toward a consistent premium level. The wines are technically perfect, reliable, and instantly recognisable on the world stage. Barolo becomes a luxury product with a clean story and a clear place in the market. The downside is obvious. Differences between producers and between slopes become less pronounced. The risk is not that Barolo loses quality, but that it loses character.

Between those two extremes sits a third path, less obvious but perhaps the one most worth fighting for. A future where capital and character can live side by side. Where investors bring stability, resources, and infrastructure, while small producers keep their place by standing out through origin, interpretation, and personality. In that model, MGAs do not become marketing stickers. They stay what they are meant to be, a true expression of terroir. There is room for diversity, even inside a more professional and better resourced region.

Which way it goes will depend on who gets to lead the conversation. On who decides what matters more: return or interpretation, scale or nuance, sellability or meaning. Barolo’s future is not fixed by rules or market models. It will be shaped by choices made now, by investors and by winemakers alike. That tension carries both danger and hope. The hope is that Barolo can hold on to both quality and character, without giving away its soul.

📊 Barolo in Numbers (2024)

- Growth in private investment since 2015: +70%

- Average price of Barolo vineyard land: €1.8 to €3.0 million per hectare

- Annual production: approximately 13 million bottles

- Average export price: €21 per 0.75 litre bottle

Sources cited in the original context include CREA, Gambero Rosso, the Consorzio Barolo Barbaresco Langhe Dogliani, and Vinous.

🕯️ Epilogue

When I stepped out of the car that day, my thoughts kept circling back to Attilio Pecchenino, to the numbers, and to the look in Caterina Cordero’s eyes.

Three million euros for a single hectare of land. But how much is a piece of history worth?

Wine has always been more than a product. It is the work of people who make choices, year after year, generation after generation. The question is whether we will still taste that story in the future, now that hectares are more and more spoken of in gold, and value threatens to outweigh meaning.

This is only one way of reading a change that touches the entire region. The conversation about Barolo’s future deserves more voices than mine alone.

For me, Barolo has always been a wine to return to. A wine to spend time with, to age, to open on the moments that matter. My hope is that it can stay that way. Not as a luxury idea, but as living wine. Even in a world where Barolo is more and more treated as a brand, and less and less as a promise.

Filed under: Second opinions? | Tagged: Barolo, bussia, Italian wine ambassador, mga, nebbiolo, pecchenino, piemonte, wijn, wijninvestering, wijnkennis |

Plaats een reactie